JCMS Teaching Dossier Vol 5 (2) Revisiting the Film History Survey Marsha Gordon, North Carolina State University

JCMS Teaching Dossier Vol 5 (2) Revisiting the Film History Survey Marsha Gordon, North Carolina State University

I regularly teach a course on “Film History to 1940” at North Carolina State University. In the fall of 2015, I began incorporating a hybrid creative and critical thinking/close reading assignment into the course, which I have found to be both pedagogically successful and much-loved by the students. The first section of the course focuses on film technology, and within this heading I pay attention to Thomas Edison and the films produced under his auspices. Working in conjunction with NCSU librarian Jason Paul Evans Groth, I created an assignment that asks students to do a contemporary recreation one of Edison’s one-shot, roughly twenty-second Kinetograph films from the mid-1890s, which were largely produced for exhibition in the Kinetoscope. The full assignment appears below.

The Edison assignment grew out of a spring 2014 foray I made into combining conventional scholarly research with media-making that was designed to take advantage of the high-tech exhibition spaces in our campus’s state-of-the-art Hunt Library. “Shooting Wars”, designed for MA-level students in a course on War Documentaries, asked students to utilize archival footage to create a three-screen installation (with sound) documenting an American conflict, which was then exhibited in the Library’s Game Lab. Extensive documentation of this project, including interviews with students, is available as an NCSU Library Story.

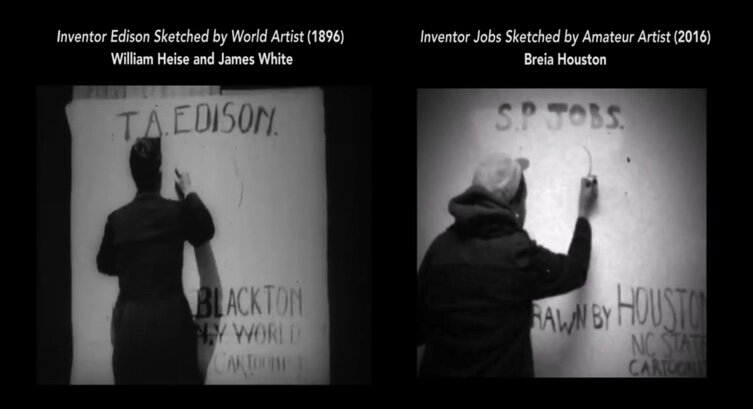

A project revolving around a one-shot Edison Co. film seemed like a good starting point for a larger class at the undergraduate level. Students pick one Edison Co. film from a list of options that are digitized and available for them to watch repeatedly, then closely study its framing, the movement within the frame, and its mise-en-scène. Students then recreate the film in whatever fashion and context they deem appropriate and engaging, using either their smartphone cameras or higher-quality cameras borrowed from the library. Key to the assignment is that I ask students not to feel compelled to travel back in time to make the film as if it were the 1890s, but rather to remake the film in the context of the present day. For example, if blacksmithing seems outmoded, what seems like a contemporary mode of work? It can either be a fairly precise remake or it can deviate from the original and provide commentary on the differences between then and now. For example, every semester at least one student has filmed a lightning sketch of Steve Jobs instead of Thomas Edison, opting to depict the person in their generation whom they consider to be the most impactful inventor of the day.

The trickiest part is making sure that the duration and timing of their remakes are right, since the students’ videos will be exhibited alongside the original Edison Co. films. Students do their best to capture timing but often some minor editing (mostly time shifting) needs to take place to ensure that the videos start and stop in sync, and for important moments to match correctly. The students upload their videos to a university drive, and my library partner, Jason Paul Evans Groth, takes the finished recreations and adds them (alongside the original Edison film) to an Adobe Premiere template that matches the 21-foot x 7-foot video display wall size of the Immersion Theater screen. (Adobe Premiere works well for this because it allows multiple video tracks and an easy drag and resizing option for multiple videos on the same template.) Of course, this same technique will work for any sized screen. Once this is done, the minor edits necessary to make the films “fit” can be done with Premiere. The process itself actually creates a collaborative moment between the librarian and the students.

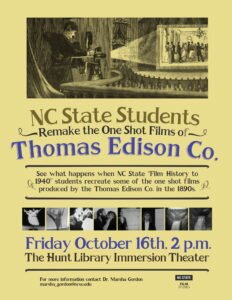

The final videos are exhibited on the Immersion Theater screen in a public space in the library alongside the original Edison Co. film. They are premiered at an event attended by the class and any other interested parties (since it takes place in an open area of the library). The videos are also available on demand for the rest of the academic year from a touchpad located in the exhibition space, allowing the students to return to show off their work or for anyone browsing student projects to see the work that they have done.

This exhibition aspect is important. Rather than making something just for their professor, the publicness of the presentation gives the students a sense of public ownership of their work that rarely happens with assignments. It certainly encourages thoughtfulness and creativity.

But this exercise, as I mentioned at the outset, is about combining critical and creative work. And so students must also write a short, three-page reflection paper about their experience and how it transformed their understanding of the Edison film. Though different from what I typically assign in any of my courses, which tends to be historical research combined with film analysis, this assignment has been one of my most successful, and usually shakes up—in interesting and useful ways—my more traditional film historical approach to the rest of the course. Anonymous comments on the assignment from end-of-semester course evaluations have indicated this. For example: “It was so nice to have an assignment that was challenged me to think differently and allowed me to be creative, something that college students don’t often get to do with assignments.”

As I continue to consider how research and the production of knowledge can extend to the broader public outside of the classroom, this assignment does several things that I consider key: it encourages the very close study of a single film for students who have likely never been asked to scrutinize such an object so closely; it compels students to think about how constraints breed aesthetic decisions; it asks students to regard the world around them in relation to the past through the close study of moving images; and it encourages students to consider how creative endeavors can be informed by academic study, especially when the result of that work exists in a public space. Watching the students thrive in this context even inspired me to push the boundaries of my own work. In 2016, I was part of a collaborative art installation, “Public Displays,” which was, true to my Film History assignment, based upon a single Thomas Edison one-shot film, The May-Irwin Kiss (1896).

If you end up trying a version of this assignment in your film history classes, I would love to hear how it goes and what modifications you make to it.

Sample Paired Edison Projects: https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/0B6lAkiArN0-ya2I0MEhiZlg0Qnc

Assignment: Thomas Edison Then/Now

Dr. Marsha Gordon

Film History to 1940

I. Video Due: Monday Sept 21 (15% of final grade)

II. Paper Due: Monday Sept 28 (10% of final grade)

III. Project Premiere Hunt Library Oct 12, 5:30pm Library Liaison/Project

Collaborator: Jason Paul Evans Groth

Part I. The creative portion of this assignment is to recreate one of Edison’s one-shot Kinetograph films, which were largely produced for exhibition in the Kinetoscope. Most of these silent films were made in the Black Maria; some were shot outdoors.

1) Each of you will pick a film from the list at the bottom of this assignment sheet. Digitized version of these films are available at http://go.ncsu.edu/edison_project.

2) Watch the film repeatedly. Study the film very carefully in terms of framing, movement within the frame, background, props, costume, & lighting. Take very careful notes—even a twenty second film has more details in it than you can remember. [Note: do not worry about missing frames or irregularities in the film you have selected, unless you want to!]

3) Recreate the film. You are not traveling back in time to make the film again in the 1890s; rather, you are remaking it today. It can either be a fairly precise remake or it can be self-aware in terms of its deviations from the original (for example, as a commentary on the difference between then and now). You may substitute costumes, locations, and props that are appropriate to your life now instead of to the time/place the film was made. [Side note: If the original film has fifteen people that appear in it, don’t worry about having exactly fifteen people if that is not feasible. If the original is about Blacksmithing, feel free to think about another kind of job that is more pertinent to the times we are living in. In other words, be creative but also thoughtful about your choices.]

Your video should be as close to the exact same duration as the original as possible. The content of your video should be staged in a fashion that is either a copy of or a commentary on the original. Again, if there are appropriate modernizations that you think would add to the interest of your film, feel free to explore and experiment here. What you will turn in will be a digital file that will be shown, side-by-side with the original, in a public area (the IPearl Immersion Theater) of Hunt Library.

Details/Technical Instructions: You may use any camera to which you have access that can record HD video (camcorder, phone camera, etc.); you may also check one out from D.H. Hill Library or Hunt Library. Remember that your video will be projected alongside the original film, so timing will be very important. When you are done making your video be sure to view it alongside the original. It may take many attempts for you to get the timing to work out to your satisfaction, so avoid shooting at the last minute.

- Your film should consist only of one shot with no cuts or edits. I highly recommend using a tripod to avoid shaky video (D.H. Hill and Hunt Library loan tripods as well as smart phone adapters for tripods).

- Edison used a circa 4:3 aspect ratio (ratio of width to height). If you choose to use a smart phone, we highly recommend recording your content horizontally (or in landscape mode) so that we can more easily replicate the 4:3 aspect ratio.

- Shoot at the highest quality possible (for example, on my older generation iPhone the highest quality I can choose in settings under Record Video is 1080p HD at 60fps—that will work just fine). We can accept your videos in whatever format your camera records them.

- Please name your file whatever your UnityID is.

- When you are done with your video, go to [Google Drive on NCSU Website]. If you aren’t signed in to Google, sign in to your NCSU account. Either drag and drop your file into the drive folder that appears or click “New” and then “File Upload” and choose your file.

- Once you have uploaded your video, immediately fill out the information on the class Google sheet: a) unity id, b) your name as you want it to appear on screen, c) the title of the original Edison film, d) your video’s title, which may be identical to the original or may be a modernization.

Title Examples:

Joe Smith, Corner Hillsborough and Oberlin Streets, Raleigh (2018), Corner Madison & State Streets, Chicago (1897)

Maya Stevens, Lunch at Talley (2018), Mess Call (1896)

Sally Bowles, Interrupted Lovers (2018), Interrupted Lovers (1896)

Jason Paul Evans Groth, our amazing library liaison, will pair your new videos with the Edison originals for our split screen exhibition. These paired movies will be shown in the IPearl Immersion Theater, one of Hunt Library’s giant public video displays.

Part II. Three (full!) page reflection paper. The following questions are just prompts for your essay—you do not have to answer all of these questions. This should be a fluid, thoughtful essay about your experience and understanding of the Edison film you selected.

What did you learn about Edison films from this process? What was it like to study a film so closely—did you notice new details as you repeatedly watched it? What did you decide to copy identically, and what did you modernize—and why? What was the hardest part of making a contemporary version of the film? Do you have any new thoughts about what the film’s makers might have been hoping to achieve? Or about what audiences might have enjoyed seeing? About the process of early filmmaking? About the limits and challenges of having to make a film of this length? Did you come to any new conclusions about what the film can tell us now about the past? What does the circa twenty-second format mean to you today as a user and consumer of moving image media?

*********************

Films You May Choose From:

Blacksmithing Scene (1893)

Carmencita (1894)

Athlete With Wand (1894)

Band Drill (1894)

Sandow (1894)

Amy Muller (1896)

The John C. Rice-May Irwin Kiss (1896)

Mess Call (1896)

Interrupted Lovers (1896)

Corner Madison & State Streets, Chicago (1897)

Pillow Fight (1897)

Inventor Edison Sketched by World Artist (1896)

Lower Falls Grand Canyon, Yellowstone (1897)

Marsha Gordon has been a professor of film studies at North Carolina State University since 2002, where she has taught courses on film history (to 1940); the Hollywood studio system; Sam Fuller, Ida Lupino, and other independent filmmakers of the 1940s and 1950s; war films; documentary and orphan films, especially of the educational variety; and women directors.